The Trump administration, working together with Elon Musk and the not-exactly-a-department Department of Government Efficiency, has sought to impose substantial cuts to federal research funding across a wide range of agencies. Federal grants can be complex both in their breadth and internal reasoning, so I thought it would be useful to have some answers to questions or misconceptions I’ve seen come up frequently. At the end I also blab a bit about my personal take on where things are going.

Preliminaries

What does the public think about government investments in research?

The public overwhelmingly supports government funded research. The most recent US polling was conducted by Pew Research in 2022. A total of 81% participants responded that government investments in scientific research are worthwhile investments for society over time; with just 18% responding that they are not worth the investments. Interestingly, in a separate question on how the US compares to other countries, just 14% responded that the US is gaining ground, while 38% responded that the US is losing ground.

What is DEI and what does the public think about it?

The precise definition of “DEI” is an area of active debate to put it lightly. I don’t want to get too hung up on language, but I think it is important to distinguish between several types of Diversity/Equity when talking about the cuts that are being considered:

DEI in hiring: hiring policies that seek to meet certain diversity goals and/or improve the working environment for certain people (e.g. affinity groups).

DEI in research communication: efforts to communicate or expand science to underrepresented groups, for example through targeted teaching or workshops.

DEI in study design: efforts to collect and understand data from underrepresented groups, for example by collecting biological data from specific populations that are otherwise hard to reach or developing multi-lingual study materials.

DEI meta-science: efforts to understand how/which policies actually do meet the desired hiring or communication diversity goals.

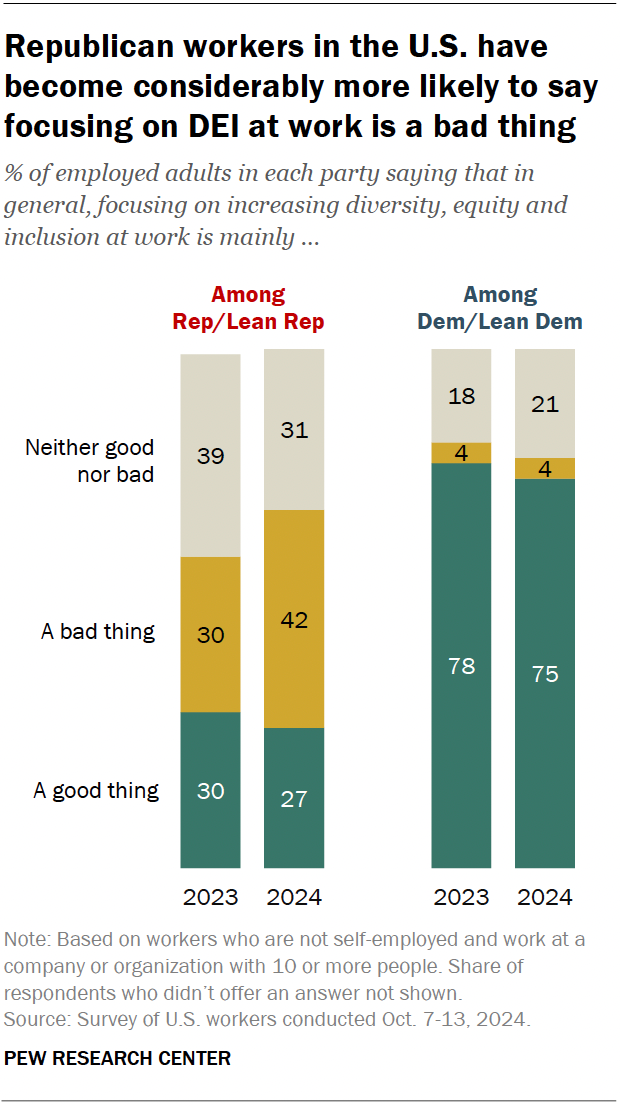

Pew Research polled topics related to “DEI in the workforce” in September/October of 2024, and the issue has a clear and unsurprising partisan valence. A plurality (42%) of Republicans think focusing on DEI at work is mostly a bad thing (up from 30% in 2023), whereas 75% of Democrats think such focus is mostly a good thing. It is therefore not too surprising that an incoming Republican administration would want to reduce spending on an issue that Republicans think is a bad thing and cut DEI-related hiring and workplace programs.

It is less clear where either the administration stands on DEI in research communication or study design, with the latter generally understood to benefit all individuals by broadening the genetic and environmental heterogeneity of the study population. Incoming HHS secretary RFK Jr, for example, has advocated for the development of different vaccine schedules for African Americans (these claims are not supported by scientific evidence), which would necessitate DEI studies designed around specific demographics. Rather than simply parachuting in with a consent form and a blood draw, such studies could in turn benefit from DEI outreach and engagement efforts to underrepresented communities (and, arguably, DEI outreach would benefit from having more people from underrepresented groups actually working in science and doing the outreach). In other words, DEI study design and communication are also part of the stated goals of this administration. Unfortunately, the language around DEI bans has so far been very vague and risks discouraging or outright blocking important research.

NIH

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) are the primary source of funding for basic and translational research into health and disease in the US. The largest changes to the NIH policy involve a reduction in “indirect” costs and cuts to specific DEI mechanisms. Let’s go through what that means.

What are F&A (“indirect”) costs and why are they important?

Let me briefly summarize how federal research funding works. The NIH regularly issues requests for funding applications on specific topics that they want to support. Academic institutions apply for these funds, typically by delegating to individual investigators who develop the research proposals. When a proposal is funded, the costs are categorized into two groups: (1) “direct” costs that go to specific components of the project (staff, reagents, etc) and (2) Facilities & Administration (F&A) costs that go to supporting more general aspects of the research environment — which are often referred to as “indirect costs”. Facilities covers costs like lab spaces, buildings, computing cores, etc. Administration (which is itself capped at 26% of the budget) covers costs like payroll, hiring, IRB/human subjects protection, etc. including a lot of administration that the NIH itself mandates. Both costs are necessary for the research to be done and it is illegal to use “direct” costs to pay for F&A spending. A research contract is work: when the government hires General Dynamics to build a jet, they pay for the hangar; and when the government hires a university to study cancer, they pay for the lab space. For more specific examples, below is an infographic itemizing some typical direct and F&A costs.

How is the NIH changing F&A costs?

Conventionally, F&A costs are negotiated between each academic institution by HHS using retrospective audits of university spending. Rather than itemize F&A charges within each grant, the institution negotiations a single “rate” that is applied across all grants. Some grants will end up using more F&A (for example wet-lab research with complex specimen storage requirements) and some grants will use less, but since most institutions have many active grants the overall rate is expected to average out.

Last week, the NIH issued a notice that immediately reduced the F&A rate to a fixed 15% across all grants, equivalent to ~13% of the total budget (0.15/(1+0.15)). The prior rate varies across institutions and states, but taking Massachusetts as an example: a total of $3.46 billion in NIH research funding in 2024 included ~$1 billion in F&A costs (i.e. ~28% of the total budget is spent on F&A). The new fixed rate would reduce the F&A budget from $1 billion to ~$400 million essentially overnight, impacting an enormous amount of ongoing research. No guidance was provided for how this shortfall is to be covered, since it is illegal for “indirect” charges to be billed directly to the grant. While people disagree on the optimal F&A rate, I have not found a single expert on this topic who believes that 15% is reasonable or sustainable.

Are changes to the F&A costs legal?

In response to the NIH notice multiple academic institutions sued the government and secured a temporary restraining order almost immediately. The full lawsuit is available online and provides many useful details on F&A costs and the relevant regulations. The lawsuit includes multiple counts but the core claims are:

The NIH is required by law to justify the new F&A rate as well as the immediate implementation of the rate and to follow certain rule-making procedures (such as publishing the proposed rule change and soliciting feedback). It has done none of these things.

A 2024 Congressional appropriation forbids the NIH from developing or implementing a modification to the F&A rate.

All agencies are generally forbidden from retroactive rule-making.

These claims seem fairly inarguable and other experts on research funding have argued that this will be an open and shut case agains the NIH (see: Stuart Buck’s article at The Good Science Project). Of course, recent history is full of cases that appeared to be open and shut but did not quite go as planned.

I’ll add one other tea leaf. The Presidential Transition Project (aka Project 2025) provides an outline of the changes sought by the new administration at every agency. It includes bulleted lists of action items for the president, the administration, the agency heads, or for Congress. The proposal to cap indirect costs is addressed to … Congress. Thus it appears that even the transition team understood that these changes must be made through an act of Congress.

Do F&A costs go to DEI?

The former dean of Harvard Medical School, Jeffrey Flier, was recently interviewed on the topic of F&A/indirect cost cuts and addressed the DEI question. Flier has previously advocated against speech restrictions (writing in The Atlantic) or DEI programs that empower them (writing in Quillette), so one might expect him to acknowledge any DEI-related abuses of indirect costs. Here is what he had to say about DEI spending (see 4:27):

The dispute is that some people think that the indirect costs have become too high. They vary among institutions in a way I can describe. And some people claim that all it is is an administrative bloat. It's just there to pay for administrators, and it's there. Some people have been saying it just pays for DEI. These are absurdities that are being claimed by people who are ignorant of how the system works.

Later in the interview, he returns to related critiques of academic research made by former health researcher and current online influencer Vinay Prasad (26:24):

But, you know, I've read some of Vinay's tweets last night and this morning about this, and I think he's gone off the deep end. And I say this as someone who's written some articles with him. He talks about biomedical research like it's a cesspool of drugs. you know, shitty scientists doing lousy work and administrators and deans who only want to get money into their slush funds. I mean, that's laughable, and it illustrates a lack of knowledge or seriousness, and that's not going to help us.

Flier goes into the details of how F&A costs are calculated and addresses other concerns, but he is consistently highly critical of the new F&A changes.

What would be the consequence of cutting F&A costs?

Since F&A costs are necessary to conduct the research and it is illegal to include them in the direct costs budget, the immediate consequence would be a massive cut in research capacity. The long term consequences are harder to game out but I would expect some of the following to happen to research institutions:

Research would become a net money loser for most universities, since they would need to fund the facilities and administration out of pocket. Most universities do not have large endowments or independent money streams to supplement these costs and would likely cut research entirely.

State universities that want to continue conducting research would need to offset these costs by raising revenue through state taxes.

Even at elite universities with large endowments, components of the endowment are often earmarked by donors for specific purposes. To the extent that endowment funds could be redirected for F&A, they would likely go towards a small core of donor-pleasing, headline-generating science that the university sees as driving donations or recruitment.

And to individual investigators and grants:

Individual investigators would need to find creative ways to shift F&A costs to the direct cost budget, making each grant effectively smaller. Shared facilities like cores, libraries, etc. that cannot be partitioned into individual direct charges would either be eliminated or be restructured as fee for service.

Each submitted budget would become much more complex, requiring substantially more time to prepare by the investigator and requiring much more scrutiny by the grant reviewers. Currently, budgets are project specific (staff, reagents, etc) and fairly straightforward to understand, with a single negotiation happening across the entire institution for F&A costs. In in the alternative scenario, every submitted proposal effectively becomes an independent negotiation for F&A costs.

Each funded grant would also be much more complex, requiring investigators to itemize, track, and report many more research costs than they currently do.

The NIH has made no indication what they intend to do with the money recouped by the cuts. It is possible that they would fund more grants, or increase the size of each individual grant. Or, as indicated in the Project 2025 agenda, the money will simply be cut.

What about grants from private foundations?

An argument made in the NIH notice is that private foundations often require much lower F&A costs than government grants. This is true. However, foundation/philanthropic funding differs from government funding in a number of key ways:

Foundation funding typically does not have the administrative requirements that come with NIH funding, such as detailed trainings, conflict of interest monitoring, and data security requirements. Thus the F&A costs for this funding are actually lower.

Foundation funding often allows for direct charges that would not be allowed by the NIH or international spending that does not make use of institutional facilities.

Foundation funding is ultimately a very small proportion of academic research funding and is thus treated more like a gift than a contract. The receiving institution is effectively subsidizing or matching the F&A costs.

A useful contrast is what happens when academic institutions partner with commercial sponsors, such as pharmaceutical companies that sponsor clinical trials. These projects are much closer in scope to NIH funding and, indeed, the company is typically required to pay the full NIH F&A cost (see discussion at 35:52). The institutions thus treat F&A costs similarly for large-scale research efforts, whether with the government or with industry. Private foundations receive a unique rate because of their special philanthropic status and their generally minimal contribution to overall research spending.

What about specific funding mechanisms?

Separate from the proposed F&A cost reduction, the administration also issued an executive order broadly against DEI policies in the federal government. It remains uncertain whether this order will apply to various efforts by the NIH to recruit individuals from underrepresented groups, such as the “Diversity Supplement” which was initially marked expired and then reinstated. Diversity supplements seek to “foster diversity in the scientific workforce” because “diverse teams working together and capitalizing on innovative ideas and distinct perspectives outperform homogenous teams”. These supplements prioritize racial/ethnic minorities, but also applicants with disabilities and those from various disadvantaged backgrounds: homeless, foster care, free/reduced lunch, first generation college, Pell Grantees, or rural areas. In the battles over DEI, it is often lost that efforts are made to draw a wide variety of disadvantaged individuals into academic research. It is hard to say how these priorities fit within the goals of the administration, which is not averse to using funding for social engineering. For instance, the Department of Transportation has circulated a memo to prioritize federal funding for communities with higher than average marriage and birth rates. Time will tell whether people from disadvantaged communities are also deemed worthy of funding support.

Why doesn’t the NIH do things like [this] instead?

Discussions about NIH reform often focus on new types of grants, but the NIH actually supports a variety of different funding mechanisms. Want to fund successful researchers rather than specific projects? The R35/MIRA aims to provide “highly talented and promising investigators” with “greater stability and flexibility”. Want to give a small amount of seed money for high-risk/high-reward science with little pre-existing data? The R21 Exploratory/Developmental grants aim to do that. Want to give a lot of money to new rising stars based solely on the strength of their ideas? The DP2 / New Innovator Award is for that. Want to fund doctors to become data scientists or data scientists to become doctors or postdocs to become professors? There’s a variety of K / Career Development grants for that. Not all of these mechanisms work as intended and the current system is unlikely to be perfect. But it’s worth keeping in mind that many ideas out there have already been implemented in some form. If you’re interested in more, I’ve previously written in more detail about potential NIH reforms here:

What are the direct benefits of NIH-funded research?

As with any research, it is difficult to precisely quantify the contribution NIH funding to science, society, or national security. The medical research advocacy group United for Medical Research (which consists of medical schools, societies, and companies) released a report estimating that each NIH research dollar generates $2.46 in “economic activity” based on a model of economic inputs and outputs. Separately, studies have shown that funding from the NIH supported nearly every (99%) approved drug from 2010-2019; that 10% of NIH funded grants produced patents directly and 30% produced articles that were cited in patents; and that there was causal evidence that NIH funding increased the net number of patents. By a variety of metrics, NIH funding is productive and ripples out into substantial medical and economic benefits.

How will NIH-funded research continue to be beneficial?

These prior analyses were all retrospective but we should also consider what NIH-funded research supports going forward, and in my opinion now is the absolute worst time to reduce funding for basic research. A key advantage that the field now benefits from is a massive amount of data on biological function through large-scale human genetic studies and high-throughput screens. Over the past decade, biobanks involving millions of individuals have mapped how individual genetic variants are associated with disease. For instance, a few months ago data from a massive meta-analysis of nearly 1.5 million individuals and >300 traits (the FINNGEN-MVP-UKB cohort) was made publicly available and searchable. Just the other week, a genetic study of kidney function in ~2.2 million individuals identified >1,000 individual associations of which >100 showed evidence of drug potential. Systematic analyses have previously shown that such associations are predictive of drugs that will be successful in clinical trials as well as potential drug side effects (see figure below). This success is in stark contrast to the prior era of “candidate gene studies”, where researchers pre-selected promising genes to test for genetic evidence, which proved to be highly prone to false-positives and cherry picking. Genetic association studies are just one example where the field has moved out of the darkness and into the light in terms of rigor, reproducibility, and data sharing; and has already benefitted translational medicine. To be clear, big data is not a silver bullet, and the thousands of associated loci need to be carefully understood to find the subset that can be targeted safely and efficiently. But it would be a huge shame to obliterate the research environment just as we have assembled an unprecedented look-up table of biological function.

NSF

In contrast to the NIH, changes at the NSF have so far focused on scrutinizing individual approved grants, either using keyword searches for DEI-sounding language or from a database prepared by Senator Ted Cruz of grants that allegedly push “far-left ideology”.

Why do NSF grants include DEI-sounding language?

A typical NSF proposal is evaluated on two components: Intellectual Merit, which describes the proposed research; and Broader Impact, which describes the benefits this research has for society and underrepresented/disadvantaged individuals. The broader impact component was mandated by Congress in the 1980's in an effort to directly justify federal spending on science, and has been in place ever since. One of the explicitly stated goals of the Broader Impact criteria is “Expanding participation of women and individuals from underrepresented groups in STEM”. Both intellectual merit and broader impact are then summarized in an overall abstract, which appears to be the content that is being scanned for DEI-associated keywords. In short, many of these grants are being flagged for directly responding to a Congressional requirement.

Is the Broader Impact section really necessary? I myself submitted (and was awarded) an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship and I have also advised several graduate students in their applications. I'll be honest that at the time I would probably have been quite happy if the section didn't exist. Not only is it one less item to complete, but it is the kind of self-reflective / forward thinking writing that tends to be difficult to do in a genuine way at that age. Now, I think spending some time writing about the ramifications of our proposed work is a useful exercise. I tell my mentees to take it seriously but not so seriously that they start telling stories. The goal is to demonstrate an understanding that we do indeed live in a society, not to act like we're going to end all racial strife and bring about world peace. I think even Trump-supporting members of Congress may appreciate this kind of reflection. One proposal I’ve seen is to require every grantee to write a yearly Thank You note to the American taxpayer for their funding. Coercing gratitude out of applicants feels disingenuous, but I think the intent here is coming from the same place: to have applicants reflect on where their funding comes from and how they are using it meaningfully. In any case, get rid of the section or don't, but it is neither fair nor good for Congress to ask applicants to write about broader impacts and then retroactively punish them for doing it.

How many flagged grants are actually DEI-related?

The Cruz database includes ~3,400 grants (out of ~44,000 grants funded by the NSF during the Biden administration) and several attempts have been made to quantify how many actually meet the stated criteria of DEI/neo-Marxism. Anecdotally, NPR has reported on multiple grants in the database that are completely unrelated to DEI: “better ways of synthesizing new medications; studying how to make self-driving vehicles safer; investigating how military service could help more women pursue science careers; figuring out why some proteins start to malfunction in ways that can lead to cancer.”. In an even more absurd example, the Times of Israel reported on multiple flagged grants that involve US-Israel partnerships, including one that studies linguistic differences between Hebrew and English. This grant was labeled as promoting gender ideology even though “the sole mention of gender in the grant’s description is in reference to the fact that the Hebrew language (like many others) assigns gender to nouns”.

For a somewhat more quantitative estimate, blogger Scott Alexander reviewed a random sample of 100 flagged grants and estimated that 40 were clearly not “woke science” (by his standards), 20 were borderline, and 40 that he considered “woke science”. Even for the 40 “woke” grants, Scott estimated that about half were “STEM Career Day type things which went too far in talking about how they would cater to underrepresented minorities”. As noted above, expanding participation to underrepresented groups in STEM is literally a component of the Congressionally mandated Broader Impacts criteria. So even by fairly generous standards, the fraction of NSF funded grants that goes to “woke science” is estimated at <3%, and many of those grants are actually responding to a Congressional mandate.

Other agencies

Important research is also conducted within federal agencies either directly or through contracted studies. While these agencies are typically Congressionally mandated, their day-to-day operation is administered by the executive branch and so their function can be swiftly undermined by terminating contracts and staff.

USAID

US humanitarian aid makes up about 0.24% of Gross National Income, which puts us both at the top of the OECD countries in terms of absolute spending and in the bottom third in terms of % spending. The majority of US global health funding comes through USAID, which accounts for ~0.5% of the federal budget and ~1% of federal spending. In addition to developmental grants, USAID also supports international health research such as clinical trials in countries with high incidence of certain diseases (whereas the NIH primarily funds research in the US). The administration currently appears to be shutting down USAID entirely by freezing grants, closing buildings, and laying off workers. As with the NIH cuts, this is very likely an illegal act because USAID is appropriated by Congress and cannot be abolished without Congressional approval. Although waivers for certain grants have been issued, with the administration tacitly acknowledging that these efforts are vital, reporting from international USAID sites indicates that the waivers are not being processed and sites continue to shut down. In some instances, participants in clinical trails have been abandoned with medical devices in their bodies that they cannot remove1. While it is difficult to evaluate the benefit of each USAID program in detail, a team of journalists and academics recently put together a report on PEPFAR — the emergency AIDS relief program initiated by the Bush administration — estimating that 7-30 million lives have been saved at a cost that is >1,000x lower than accepted spending in the US. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has, until very recently, strongly advocated for USAID funding, calling it “critical to our national security”.

Department of Education

Over a hundred contracts have been cut at the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) and Institute for Education Sciences (IES) within the Department of Education. The IES conducts randomized studies of educational outcomes as well as longitudinal educational assessments. The contractual cuts appear to be largely arbitrary and include multiple high-quality, longitudinal cohorts such as the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), and the Common Core of Data (CCD) which itself supports the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP, typically referred to as “The Nation’s Report Card”). The Good Science Project has a discussion of the importance of the studies and datasets being cut, and an education policy analyst from the first Trump administration is likewise critical of the cuts. In what is looking like a pattern, IES was Congressionally mandated in 2002 so formally closing it is illegal, but defunding its core data collection contracts effectively does the same.

Some closing thoughts

I want to end with some big picture takes but I also recognize that the world is not exactly begging for more opinions from latte-sipping coastal university professors. If that is not your thing I suggest to stop reading here, consider this a trigger-warning of sorts.

In my view, an orderly political system should have candidates who run on a policy platform and, if elected, implement those policies with cooperation from Congress and within the scope of the law. That gives us, the public, a kind of randomized trial of different policy agendas to inform our future voting choices. But that is not what we are getting right now. The president did not run on a platform of slashing research, in fact, he directly rejected any connection to Project 2025, the policy blueprint these cuts build off of. Even after the election, there was talk of boosting US research & development and American technological might. So we have an agenda that was hidden from voters and is now being implemented chaotically (see example below), in direct contradiction to Congressional mandates, and very likely in violation of the law. Usually, the public responds to this type of political overreach by rapidly losing support for the president (which is already happening); sweeping his party of the Congressional majority in the mid-term election, leaving him unable to pass durable policy; and then electing a backlash president to undo the changes. This is more or less what happened through the 2016 term and we are on track for an accelerated version of the same.

So what are they trying to achieve? In conversations with DOGE supporters I've generally encountered two positions:

Just relax and give it time, Elon is just shutting everything down to identify what is wasteful and will put the useful programs back in.

We had to suffer through woke science (with examples ranging from sympathetic cases like "I was reprimanded for expressing skepticism that our corporate diversity efforts are effective" to weird hyper-online fixations like the "Gen-Z Boss and a Mini" TikTok video), now we won, so we get to make scientists suffer.

The first view may make sense when cutting costs in a company with a singular mission where mission critical components can be identified quickly, but it makes very little sense when talking about an entire research landscape that largely operates through tens of thousands of independent projects. What happens while everything is shut down? Excellent funding applications that took months to develop are summarily rejected because their mechanism was cancelled; high-scoring grants are passed over for funding because the review council cannot meet; effective drugs are delayed for approval because the FDA has a staff shortage; longitudinal cohorts that have been collected for decades collapse and their data becomes polluted; and — most importantly — the next generation of talented people who planned to pursue research for the public good are cruelly let go or not hired and drift away. In most cases we may not know for years that a study or a dataset was important and should not have been abandoned. And because the whole thing is being conducted without rigor, even when cuts increase efficiency they will be confounded by all the other functions grinding to a halt.

I also find it difficult to square the first view with Musk's erratic online behavior (to the extent that he even seems to be unaware of what he himself is doing; see above tweet); his recent tweet that he "spent the weekend feeding USAID into the wood chipper"; or OMB Director Russ Vought's pre-election promise that he wants “the bureaucrats to be traumatically affected … we want to put them in trauma”. Elected officials should enact policies that they actually believe to be productive rather than using the government to “put their enemies into trauma”. It is possible the administration eventually re-orients towards genuine reform. But if it becomes clear that trauma is the real goal, then academics need to start advocating directly to the public about the danger and waste that it brings, and start building the foundation for a scientific resurgence. Equally important, researchers in pharma and biotech — people who often came out of the same NIH and NSF pathways, and who rely on foundational discoveries made by basic science — need to speak up too.

I’m going to hold back commenting on what is happening to USAID because much of their work is not research related and is not my area of expertise. But gleefully abandoning clinical trial participants with no way for them to remove medical devices is one of the most vile and senseless acts of cruelty by the US government that I have seen in my lifetime.

One (semi) important detail -- capping the F&A rate to 15% actually means *less* than 0.15/1.15 of the total expenditure is for indirect costs, because not all direct costs carry F&A. At MIT, across all research grants, only about 70% of direct costs carry F&A, so this is a pretty significant difference.